|

There are two former Views that are essential in understanding the role of retailing, free enterprise and capitalism in driving the growth of the prosperity of the whole of society:

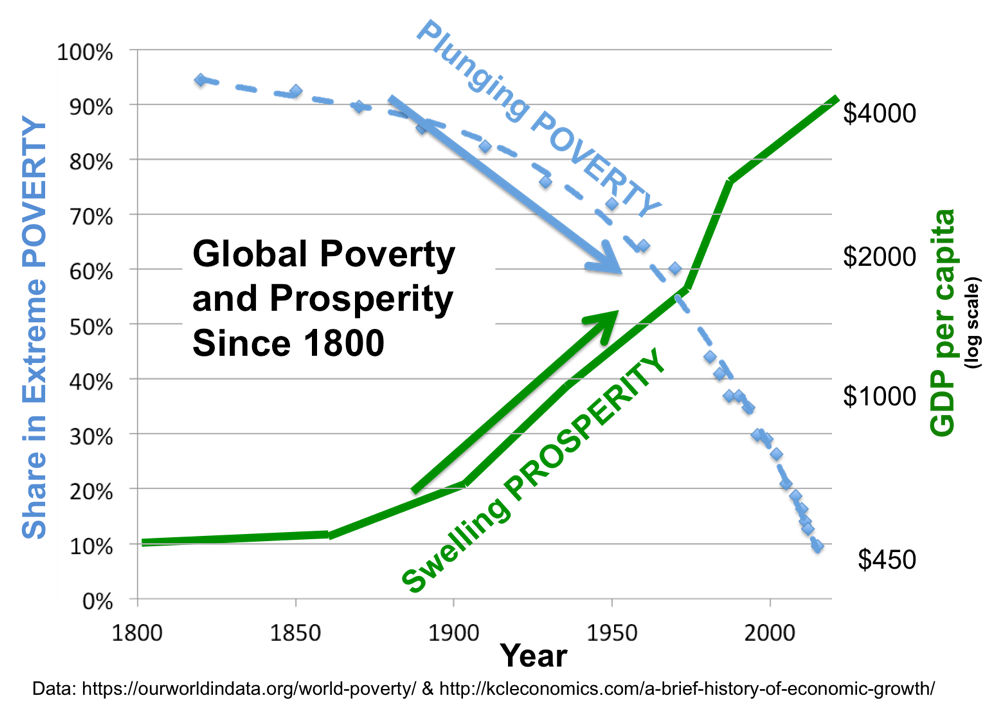

What we want to do here, is to knit together the content of those two issues, to document and explain the improvement of the lives of both the rich and the poor over the past 200 years. Also, to bring more focus to the individuals who very understandably did not welcome this growth, per se, primarily because it upended their own historical practices, and role in society. First, the indisputable facts for both the rich and poor classes - but not necessarily everyone!  Bear in mind that this chart represents the global condition of the human race, not just this or that country, or this or that segment of the population. The significance of this, first in terms of poverty: this is the share of people across the world living in extreme poverty. That share has fallen from 90+% to less than 10% of the global population, over the past few years. In order to achieve such shrinkage of the global poverty total, requires more massive changes in very large population countries with large impoverished populations, than simply the "tag along" poor in very wealthy countries. There, the poor often live much better than that same cohort in the very poor countries. The plunging rate of poverty is a fact not well recognized by a large share of the relatively prosperous in objectively more prosperous countries. To the extent possible, we will avoid political commentary here, but just stick to the documented facts - and history. But putting poverty into context encourages more realistic views of the second half of the chart: the soaring rise in prosperity. The old saying that "a rising tide lifts all boats," has been skewered as if it is not solidly founded in fact. Some boats are rising very fast, and very high, while others are being stranded on the beach. But those strandees represent a shrinking share of all societies, but especially of the most prosperous societies. The reality behind that discouraging, but shrinking share, is the purpose of this Views. Our goal is to shed some further light on those that selfishly pull society forward while leaving some less pulled forward than others. A much broader view of economic disaster is needed. For our purposes here, we will use the 100 year old history of retailing as a foundation, adding to that a recent history of one major company, Nike, and then generalizing "the failure" principle of the "laundering of free enterprise." That is, the purging of what doesn't properly serve the population well in a free enterprise capitalist society. History of Retailing - The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America The history of retailing, which has played a major role in society for the past century, was reviewed in Retailing: the Trojan Horse of Global Freedom and Prosperity. Briefly, as explained by Marc Levinson, two genius brothers inherited the tea business of A&P, and started into the general grocery business early in the 20th century, building the first billion dollar business in the world. Their driving principle was not profits, driven by margin on sales, but rather return on investments. This meant minimizing investments in buildings, land and inventory, and driving massive sales, with limited margins, through spartan facilities, giving a healthy return on investments with very limited return on sales. Their problem was the super-efficient business model not only was very profitable to them, but was super attractive to shoppers because of low prices and large selections. However, their success drove thousands of inefficient businesses, many of them "mom-and-pop" stores, out of business. Those inefficient competitors banded themselves together in various associations, and appealed to various government agencies, through force of law to stop A&P. The battle against efficiency by the inefficient continued for decades. The supermarket was the fourth retailing revolution through which George and John Hartford had guided the Great Atlantic & Pacific. They were by no means the inventors of the large self-service food store. Their contribution came in figuring out how to use this new format to increase efficiency and lower costs. The spread of supermarkets and the industrialization of food production were good news for families of modest means... poorer households show[ed] startling improvements in the quality of their diets. American families ate better at far lower cost than ever before, in part because they had to pay much less to move their food from farm to table. The rise of the food chains was especially important to African-Americans. While the Hartford brothers were no more egalitarian with respect to race than most other Americans of their era, a disproportionate number of their stores were in older urban areas occupied by working-class blacks during World War II and the years thereafter, providing reasonable prices to shoppers who otherwise faced extremely high food bills from independent inner-city stores. Chain-store taxes, anti-discounting laws, and laws such as the Robinson-Patman Act, all crafted to keep shoppers from benefiting from the efficiencies created by big businesses, effectively taxed consumers so that small, inefficient wholesalers and retailers could survive. The consumers most affected, inevitably, were the least affluent. During the Great Depression, roughly half the urban families in the United States spent one-third or more of their incomes on food. [The judge] acknowledged that John Hartford's strategy of trying to lower gross profits, or markups, saved money for shoppers, but he thought [this] created unfair competition for other retailers. He disapproved of A&P's aggressive bargaining with suppliers, finding it to be an unjustified source of competitive advantage. The fact that consumers benefited, he ruled, was not relevant to the question of whether A&P was violating antitrust law. Levinson, Marc. The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America (Kindle Locations 3935-5019). Macmillan. Kindle Edition. The drive for efficiency did not affect just the retail store, but pushed all the way back up the supply chain from the delivery to the store, distribution centers and right on into the corporate suites of the major brands. Actually, the vast exposure to shoppers in mass merchants even drove the success of radio and TV, by providing a rich source of revenue to media companies, (radio, television, print, etc.,) from the major brands seeking to speak to their audience through "reach and frequency," even before they reached the stores. (And VERY competitive that seeking is!) I seriously recommend that anyone intending to understand how and why bricks-and-mortar retailers behave today, in the way they do, read Marc Levinson's book in full. I have emphasized here A&P's focus on efficiency, above all else, and the general attacks on A&P, inspired by their inefficient competitors using government to impede, and attempt to destroy them. I haven't emphasized here the almost incredibly paternalistic relation the company had to their employees. It was a great company, that virtually/spiritually died, with the death of the founders in the early 1950's, even though their liquidation bankruptcy filing didn't occur until 2016. But the main point here is that A&P - and like retailers - led a global revolution that made possible a healthy section of both of the "Plunging Poverty/Swelling Prosperity" curves cited above. They did it through what Joseph Schumpeter called "creative destruction." What that means is that when there is a massive change in efficiency of something the human race urgently needs, older, more inefficient methods are going to be destroyed, even with the full force of the government trying to stop the progress. That means huge numbers of people lose their jobs, through business bankruptcies wiping out the inefficient players who either can't, or won't recognize the truth about what is happening. These "dying" businesses need to either become more efficient themselves, or for the benefit of all of society, they vanish into the ash can of history. Failure is the natural cure for the ills of free enterprise capitalism. And the proper source of that "cure" for inefficient businesses is vigorous competition by other, more efficient businesses. All the destruction is stuff and piffle, in comparison to all the creativity at retail, the increasing wealth and prosperity of all levels of society. Notice particularly, the anti-chain store regulations and lawsuits, "effectively taxed consumers so that small, inefficient wholesalers and retailers could survive!" Furthermore, "The consumers most affected, inevitably, were the least affluent." The efficient, chain store was a great boon to the poor, the less affluent. And it ultimately triumphed against its inefficient competitors. Global History of Modern, Industrial Companies In a Harvard Business Review article, "The Living Company," Arie De Geus reports on research for Royal Dutch Shell into what leads some businesses to survive and others not. Commercial corporations... have been around for only 500 years. In that time, as producers of material wealth, they have enjoyed immense success. They have sustained the world's exploding population with the goods and services that make civilized life possible... However, most commercial corporations are underachievers... Consider their high mortality rate. By 1983, one-third of the 1970 [13 year-old,] Fortune 500 companies had been acquired or broken into pieces, or had merged with other companies... [However,] we have evidence of much greater corporate longevity. Japan's Sumitomo has its origins in a copper-casting shop founded by Riemon Soga in 1590. And the Swedish company Stora, currently a major paper, pulp, and chemical manufacturer, began as a copper mine in central Sweden more than 700 years ago. Examples such as these suggest that the natural life span of a corporation could be two or three centuries—or more. What is so special about long-lived companies? "All happy families resemble one another," Tolstoy writes in Anna Karenina. "But each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." What I have come to call living companies have a personality that allows them to evolve harmoniously... Throughout, living companies produce goods and services to earn their keep in the same way that most of us have jobs in order to live our lives. Our team found 30 companies scattered throughout North America, Europe, and Japan [that had been around since the late 1800s.] The companies ranged in age from 100 to 700 years. And 27 of them had reasonably well documented histories, including DuPont, W.R. Grace, Kodak, Mitsui, Sumitomo, and Siemens... we found that across the Northern Hemisphere, average corporate life expectancy was well below 20 years. Only the large companies we studied, which had started to expand after they survived infancy—during which the mortality rate is extremely high—continued to live on average another 20 to 30 years. It appears that in the corporation we have a species with a maximum life expectancy in the hundreds of years but an average life expectancy of less than 50 years. It is hard for people with career lifetimes often longer than the lifetimes of their employing companies, to recognize that the elephants stomping around the economy will mostly die before their employees do. What this means is that "creative destruction" is alive and well, on both the destruction side, as well as the creative side. This certainly doesn't mean that all the people losing their jobs are at "fault." Nor are the businesses "evil" - other than maybe some with less than intelligent efforts standing in front of the tide of history screaming, no, No, NO!!! Go back! There is no "back" in history. But never forget the overall balance of "CREATIVE destruction." In another context, Ross Anderson noted that, "Mass extinctions serve as guillotines and kingmakers both." (Aeon) Entrepreneurial Creative Destruction - Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike To personalize the creative side of creative destruction, consider the long career of Phil Knight, the entrepreneur that built the global Nike business. For the first 18 years of his building what began as a shoe business - selling shoes from the trunk of his car, he lived on a razor's edge in terms of even business survival. Cash flow issues were nearly killing as his business grew rapidly, year after year. Needing to double his orders for shoes, months before the money from selling them would come in, it was a tightrope, familiar to very many, essentially unfunded entrepreneurs. Unfunded in this sense meaning they have no resources to turn to, other than the money coming in the door. Then there is short term financing from banks, who care less about growth, than solid capital assets, #1 being money in the bank, or assets that can be reasonably converted to cash - outside the business operations - in a "short" period of time. Phil Knight's long walk on the tight-rope nearly ended in disaster when his competitors conspired to get the government to impose an exorbitant tax on his imports. The other mortal threat was the need to expand the budding global network of factories, now under Nike control. The solution to both problems was to go public, selling stock to investors very willing to own a piece of the future of Nike. The idea of selling stock had been soundly resisted for years, by the Nike management team. To understand the thinking behind this, listen to Phil "explain:" It seems wrong to call it "business." It seems wrong to throw all those hectic days and sleepless nights, all those magnificent triumphs and desperate struggles, under that bland, generic banner: business. What we were doing felt like so much more. Each new day brought fifty new problems, fifty tough decisions that needed to be made, right now, and we were always acutely aware that one rash move, one wrong decision could be the end. The margin for error was forever getting narrower, while the stakes were forever creeping higher—and none of us wavered in the belief that "stakes" didn't mean "money." For some, I realize, business is the all-out pursuit of profits, period, full stop, but for us business was no more about making money than being human is about making blood. Yes, the human body needs blood. It needs to manufacture red and white cells and platelets and redistribute them evenly, smoothly, to all the right places, on time, or else. But that day-to-day business of the human body isn't our mission as human beings. It's a basic process that enables our higher aims, and life always strives to transcend the basic processes of living—and at some point in the late 1970s, I did, too. I redefined winning, expanded it beyond my original definition of not losing, of merely staying alive. That was no longer enough to sustain me, or my company. We wanted, as all great businesses do, to create, to contribute, and we dared to say so aloud. When you make something, when you improve something, when you deliver something, when you add some new thing or service to the lives of strangers, making them happier, or healthier, or safer, or better, and when you do it all crisply and efficiently, smartly, the way everything should be done but so seldom is—you're participating more fully in the whole grand human drama. More than simply alive, you're helping others to live more fully, and if that's business, all right, call me a businessman. Maybe it will grow on me. Knight, Phil. Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike (Kindle Locations 4976-4990). Scribner. Kindle Edition. Actually, going public not only made all the original owners of Nike multi-millionaires, it provided funding to settle the government's "extortionate" demands. It also provided funding for building/opening new factories around the world, lots more Nike stores, and support for the exploding (in a good way) operations of Nike across America, and around the world. Was this helpful to Nike's competitors? Mostly not. It is amazing how many people think that businesses are evil because they become huge and profitable, and their owners make fortunes. At this point, Phil Knight is worth $10 billion, and his business has created many millionaires, and hundreds of millions of satisfied customers. The basic driving force of competition is selfishness! The whole point of winning is looking out ferociously to WIN! The concept here was deeply engrained in the culture of Nike. Pre was one of their sponsored runners: Pre was most famous for saying, "Somebody may beat me—but they're going to have to bleed to do it." Watching him run that final weekend of May 1975, I'd never felt more admiration for him, or identified with him more closely. Somebody may beat me, I told myself, some banker or creditor or competitor may stop me, but by God they're going to have to bleed to do it. Knight, Phil. Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike (Kindle Locations 3921-3923). Scribner. Kindle Edition. Sometimes, people think, well that isn't very Christian! Au contraire! Anyone who does not provide for their relatives, and especially for their own household, has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever. (1 Timothy 5:8, New International Version - NIV) The reality is that any good businessman/capitalist is very selfish. However, they are also well aware that looking after their own interests, begins with looking after the interest of others, otherwise known as customers. Hence, the vicious inter-business battles over things like pricing, product design, etc. All other things being equal (and they often are not,) the lowest price wins the competition to serve the customers. (For a wider discussion of pricing issues, see: Evolving Brands and Retailers; and Mind Your Pricing Cues, HBR) Winning at legitimate business is always about serving customers better, and more efficiently, than the competition serves them. Even driving your competition into bankruptcy is a good thing, if done through serving your, and their, customers better. Guess what? Customers are supremely selfish, too! Each, looking out for their own households. It is this overwhelming, and natural selfishness, that drives the welfare of the human race. Pretending that the super-wealthy have somehow ripped off society to become that way is insane. And no point in thinking, well, we need to put somebody in charge of supervising these greedy people. Government would have destroyed A&P if they could have. And government would have destroyed Nike, too, if they could have. This doesn't mean that government is inherently evil, just that it's reported benefaction becomes more doubtful, the bigger it gets. And when it says to the entrepreneur, "You didn't build that!" one can be sure that it isn't acting benevolently toward the citizenry - especially the very poorest of the citizens. (See the A&P example above. This shouldn't be taken as a blanket condemnation of government. But when government gets busy salvaging businesses headed for bankruptcy, they are depriving the successful businesses of their right to serve the customers the losers had not properly served. There is NO business "too big to fail." The bigger they are, the more their failures will benefit their properly managed competitors, (and the failing business' own customers.) Once you understand these matters, and how you and the rest of society have massively benefitted from the cleansing of the free enterprise system by bankruptcy, you may sympathize with the losers. Also note that often enough, large winners had multiple losing experiences before the big win. Losing is NOT permanent. It is part of the past, and can be the foundation of the future. And employees can move to the new companies - especially to startups, on the grow. What does this all mean for the future of retailing? Never forget the devastating slaughter of small businesses, beginning with local, neighborhood markets, that was wrought by the supermarkets. That "slaughter" was actually driven by efficiency and the striving to serve shoppers better, with larger, more efficient stores, delivering a lot more choices, and at much lower prices. That process, in the first half of the 20th century, led to the drive for efficiency and low prices by Walmart, in the second half of the 20th century. The results of that were the world's largest retailer, with nearly a half trillion dollars of annual sales. Walmart began by selling general merchandising with the same obsessive drive for low prices as A&P had with groceries. Late in the 20th century Walmart expanded from general merchandise with an aggressive drive into groceries. GROCERIES DRIVE TRAFFIC, PERIOD!!! It is the #1 need of the human race! Without going into all the why's and wherefore's, let's just say that the ideal bricks-and-mortar store of the future, will be a super-convenience store, along the lines of Wawa in the Pennsylvania market. The ideal neighborhood store will probably be about 10,000 sqft, with maybe 3,-4,000 items in the store. Note that Costco sells as high as one million dollars per day in some stores, with only 4,000 items. This is not surprising, given other super-performers like HEB Central Market and Stew Leonards, limited selection Big Head stores. The problem is that bricks-and-mortar stores swelled massively in the second half of the 20th century, primarily to drive item selection, from a few thousand to 50,000+ items. That drive was partially driven by responsiveness to shoppers, but far more driven by responsiveness to major brand suppliers, who necessarily used the store as ground zero in their determined battles with their competitors, the other major brands. That reality drove self-service retailers to cater to their brand suppliers, more than to the shoppers. The result of this was the long term evolution of self-service retailers, to actually become merchant warehousemen, relying on unpaid stock pickers, aka, shoppers, to retrieve their own purchases from the warehouse, aka store. This accurate characterization is NOT denigratory, but reality. It is necessary in order to understand the creative destruction spreading through modern retailing, known as Amazon!!! And that creative destruction is very far from over. There are two basic forces at play here in the war between bricks and clicks. The first is shopper choice, that is, how many options for every item you sell to shoppers, will you offer? That is not just how many brands, colors, flavors, sizes, etc. But how many named items will you offer in a category, or in the whole store? Bear in mind that massive item counts were NOT driven by shopper demand, but by brand funding of their merchandising efforts within the store, including paying for advertising in the stores' circulars. The reality is that if a large item count drove the bricks survivors of the future, they are ALL TOAST!!! Amazon offers 50 million items, and growing by leaps and bounds. Game OVER then, if it is all about item count. But the bricks-and-mortar store has always had certain advantages that cannot be overcome, online. The most important of these is immediacy. It is perhaps surprising that "ONE item" is the most common basket size, in nearly every store in the world. And people buying ONE item on a shopping trip, are most often doing so because they need it right now! That is, immediately, if not sooner. (Or very soon, at least. ;-) Thus, just as Amazon has the edge - and always will - on item count, bricks stores have the edge on immediacy. However, merchant warehousemen, historically, have cared little for small basket shoppers. In giant stores, there is a tendency to ignore the quick trippers - the single largest cohort of shoppers in the store. In fact, given the potential power of shoppers who buy five or fewer items, that rather than catering to these shoppers in their "warehouse," they instead began to build convenience stores in their parking lots. And this wasn't until decades after the convenience store industry was roaring ahead to massive competitive success of their own! A more relevant response to the Amazon challenge has been to add an online order capability, with pickup at the store, or delivery by existing delivery services. Sometimes this is referred to as click-and-collect, or buy-online-pickup-in-store, BOPIS. I was an early champion of this movement myself, for many good reasons - until I observed the uniformly disastrous roll-out by major bricks retailers. The problem for the bricks retailer is that their highly efficient logistics system is built on aggregate delivery (mostly pallets) to the store, where they pay their own stocking clerks to move the merchandise from the delivery dock to the displays across the store, and then rely on free labor from shoppers to pick their items, no pallets, to bring to checkout for payment, etc. Now, with click-and-collect, who is going to pay those de-stocking clerks to pick the online shoppers' orders and deliver them to the pick-up location, and especially if it is curbside? One can see reasonably operated online retailer sites, but of what I have seen (many,) the final mile of these programs are unmitigated disasters! When you look at the entire logistics system, it is obvious why. On the other hand, Amazon has built an entire logistics framework built on not only warehouse automation, but delivery of even single items to single shoppers. Bricks retailers, and apparently their advisors, act like they don't even know what the problem is. (It is a difficult, possibly intractable problem.) However, to my mind, difficult, "intractable" problems also spell massive opportunity. I discuss these matters in some detail in Chapter 1 of the new, second edition, of "Inside the Mind of the Shopper." I have been telling people for some time that I would like to assist someone to build the first convenience store with a 500,000 item count! Seriously! What I describe in that first chapter is a step-by-step process to evolve a 50,000 sqft supermarket to a 10,000 sq ft store-of the future. I won't describe that process here, but call attention to the second chapter, by Mark Heckman, a lifelong super-marketer, who supplements my evolutionary process with many points not immediately obvious to a non-retailer scientist. I should point out also my acerbic commentary in Chapter 3, on Amazon's push into bricks retailing with their bricks book-store in Seattle. I have expected for years, that as Amazon, at their own leisurely pace, launches an assault on bricks-and-mortar stores, eventually they most deal more realistically with the immediacy strength of bricks, by having their own stores. The Seattle Amazon Books was more of a technology store, like Apple, with a halo of books. It hardly addressed the urgency of food retailing. But now Amazon has announced Amazon Go, which looks from pre-opening promotion, to be very nearly exactly my specification for the "store of the future." As soon as I can get inside, to more closely evaluate what can be seen from inside, I will send an update. The new wave of creative destruction is basically being visited upon a wide variety of bricks retailers. It should be obvious that Amazon is a very competent online retailer, and is now moving to be competent in the bricks world. Their new Amazon Go bricks store, completely eliminates the checkout process: grab what you want and leave. Whatever you have taken will be charged to you as you remove it from the shelf - and refunded if you put it back! This should scare the daylights out of any other bricks retailer - ELIMINATION of one of the most frustrating and disliked parts of the bricks shopping trip - the checkout. Remember Bezos' early patent on "1-Click" purchasing? How many years ago was that, and what have YOUR responses been since, mister bricks retailer? Since Amazon's single item sales to shoppers is lubricated from supplier to shopper, how can a bricks retailers pallet logistics system, that ultimately requires the shopper to be their own stock picker - without pay - to realistically respond to the Amazon bricks store. Not to mention the fact that hired or bought online retail businesses have the same blindnesses as even the giant bricks retailers, plus can't possibly be very effective in competing with Amazon, with their own online retailing expertise This all taken together, along with a lot more, means that the current wave of creative destruction is well launched, with Amazon being the creative, with a lot of bricks retailing destined for destruction. Leaving you with two final thoughts:

Here's to GREAT "Shopping" for YOU!!! |