It helps to think about retailing, beginning with its basic elements. The driving force behind it is the needs and wants of people. Other people have produced those needs and wants, and it is a matter of getting the stuff together with the people who want and need it. Of course a driving force behind the small store movement is the effort on the part of retailers to get the stuff closer to where the people are, rather than having it in huge stores, where shoppers may have to travel some distance to get access to their needs and desires. But there are other important factors here, relating to what happens once the shopper gets to the store and goes inside.

First of all, just consider the view when the shopper steps inside:

It doesn't matter whether it is a large store (supercenter on the right) or a small store (convenience store on the left,) the shopper is going to want to purchase only a small portion of all the items in the store. The twin challenges facing the shopper are:

- Where in the store are the items I want to buy?

- And, when I get there, which one(s) will be right for me?

We have dealt with these two issues extensively here in the Views in the past. But looking at these two photos illustrates an important point: Unless all you are looking for is something to drink and a snack to go with it, the store on the left may not fill your needs. On the other hand, the odds of the store on the right having anything you might want, is much higher. This is the foundation of the solid principle that very large stores with massive merchandise offerings are very attractive. That is, they ATTRACT shoppers. But the attraction will be all for naught if, upon arrival in the store, it is not clear just where they should go.

On the other hand, for the smaller store, attractiveness can be increased considerably by apparently having a larger array of merchandise. The emphasis here is on the apparently, that is, seems like, or it appears that. One way to add merchandise without cramping or cluttering the shoppers' space is to put the merchandise where it can be seen, but not intrude on the shopping process. In the store on the left, for example, placing merchandise on blank walls, high on the perimeter, might create the image of a more generously stocked store, without actually intruding into the shoppers space. Also, allocating some of the existing slow moving space to a few new categories might be very helpful. Bear in mind that there are stores with no more SKUs than in this C-store, and yet hit a 100 million dollars a year in sales! THINK!!!

The point is that a small store can compete more effectively with a larger store by increasing at least the appearance of more merchandise – especially additional categories, while the larger store can compete more effectively by enhancing navigation and selection. The larger store is a winner on attraction, but it's selling juice is seriously attenuated.

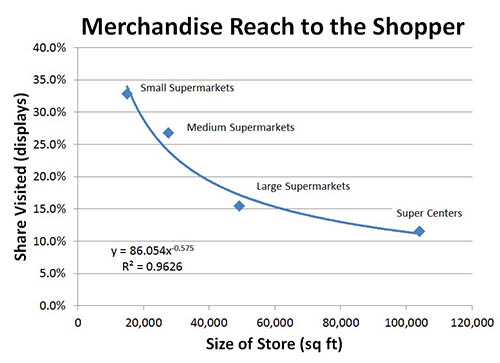

So let's see how this translates into how shoppers use stores of varying sizes:

From the small C-store to the large Super Center, there is a steady fall-off in the share of the store visited. In increasing the size of the store by a factor of five (20,000 to 100,000 sq ft) the coverage of the store by the average shopper drops by a factor of three (33% to 11%.) Hence, the title of this Views: If you build it, they will NOT come.

The comments about attractiveness, navigation and choice are intended to put you in mind of what is behind the, if you build [a much larger store,] they will NOT come [to all the displays inside.] This is a solid principle, and with a .96 correlation we can be quite confident of it. However, retailing is an incredibly complex issue, and the issues cited—attractiveness, navigation and choice—are by no means all that affect the issue of how much of the store shoppers will come to.

For example, drug stores do not fit on this curve, almost certainly because the merchandise profile is very different than for grocery stores. In fact, even with the high correlation, it would not be unreasonable to think that Super Centers do not properly fit on this chart, since without those, for supermarkets alone, the relationship is more linear in nature.

The fact is that I am often gratified to get correlations even in the .20 - .30 range: too large to consider the result to be just random noise, but not large enough to conclude that there is a clean relationship, unperturbed by the dozens of other possible variables. It is my opinion that the greatest advances in understanding of retailing are likely to be found in just such cross store studies, possibly for entire chains and ultimately allowing modeling of retail performance across the global industry, as we have done inside supermarkets alone. (See The Power of Atlas: Why In-Store Shopping Behavior Matters.)

Here's to GREAT "Shopping!"

Your friend, Herb Sorensen