|

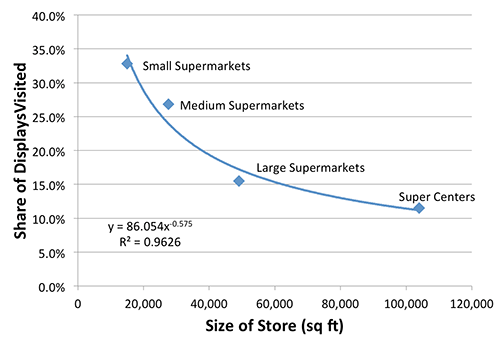

The problem I am detailing here is a serious problem for any business, but is especially serious for bricks-and-mortar retailers and will have a devastating impact in their competition with online retailing. This issue of the Views documents clearly the structure of the problem. Another pending issue (soon) will outline in some detail how exactly the problem can be solved, by any major retailer who expects to survive/thrive over the coming decades. That isn't to say that there are "decades" to formulate reasonable responses. In a $15 trillion global industry, there will be significant options for survival - of which I will outline three basics. Meanwhile, bear in mind that I am absolutely bullish on "bricks" retailing, (just as I am bullish on online retailing!) A favorite mantra is, "As long as people live in bricks-and-mortar houses, they will be shopping in "bricks-and-mortar" stores!" Take heart, but keep your wits about you. Many around may not. First, a brief definition of "parked" capital: It is simply capital that is not being productively employed, or more realistically, is producing only a tiny fraction of what it could be producing. In this sense, any business that might be delivering double digit returns on capital invested in the business, but holds capital in conservative investments like bonds, with single digit returns, has essentially parked the capital in bonds, for example. This is of course a reasonable strategy when accumulating/holding capital pending major investments, or as insurance, guaranteeing liquidity for the firm in contingencies. But sunk capital, invested in non-financial assets, that simply sits there doing nothing much of anything, in terms of delivering profits, is fairly considered parked capital. As Sancho Panza said, "Whether the stone hits the pitcher, or the pitcher hits the stone, it's going to be bad for the pitcher!" Think of a parked capital business competing directly with a non-parked capital business. In such a situation, the parked capital business is the "pitcher," and the non-parked is the "stone." It is going to go bad for the pitcher-bricks retailer, with massive parked capital. Background What has been wrongly seen as a clash between online and "bricks and mortar" retailing, is in reality not a clash, but the early adjustment of a long overdue evolution in bricks retailing. The convergence of online and bricks now underway, will reconfigure retailing built on the "unpaid stock-picker shopper." This form of retailing came into being with the massive shift to self-service retail 100 years ago. At that time, retailers gladly sloughed off the "stock-picking" they and their staff had formerly done for shoppers (paid staff did the "stock-picking" for the shoppers, before the early 1900s.) With self-service, the shoppers would do it for themselves - at no charge to the retailer. The new self-service retailing industry pushed retailers into becoming merchant-warehousemen, using unpaid shoppers to pick the shoppers' own merchandise from the store shelves, while the merchant warehouseman charged suppliers, whether directly or indirectly, for access to the sales engine (the store,) and sold them (the suppliers,) ancillary marketing services - for example, ad space in neighborhood weekly flyers, produced and distributed by the retailers. In this way retailers became merchant warehousemen, with their principle source of profits being their suppliers; not their customers!!! This is the origin of low margin retailing - designed to drive sales volume, revenue, from the shoppers, with profits deriving primarily and directly from services "sold" to the retailer's suppliers. The shift of labor from paid staff, to "free" shoppers, helped reduce expenses, and prices, in these new self-service stores. This also led to a restructuring of what was going on in the store, as self-service stores grew from a few thousand feet in size 100 years ago, to tens or hundreds of thousands of feet today, the retail mindset ingrained in the industry from 100 years ago became, and remains: "Pile it high, and let it fly!" This mantra made a lot of sense in the beginning, and the growing demand of a growing society, with increasing prosperity, made "pile it high," a very profitable retail strategy. "Pile it high" Created Vulnerability for Bricks-and-Mortar Retailers The reason for the vulnerability is that... ... it led them to massive "PARKED" capital. There are two major forms of this parked capital. The first of these is the "Parked Real Estate" Capital. Here is some data about the "buildings" portion of the parked capital, as illustrated in, "If you build it, they will NOT come!" These are the hard facts about the building of larger and larger stores. The larger the store, the less of it shoppers will visit:

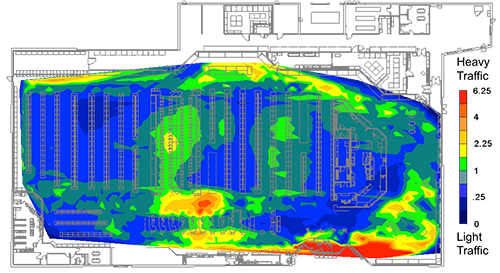

The data shows that even the smaller stores only get shoppers to visit perhaps a third of their displays, and for very large stores this plunges to closer to 10% of the store visited. Long ago, when we began showing retailers shopper density maps of their stores, illustrating where shoppers spent most of their time, one of the questions most commonly heard was, "How can we get more shoppers into these poorly visited aisles?"

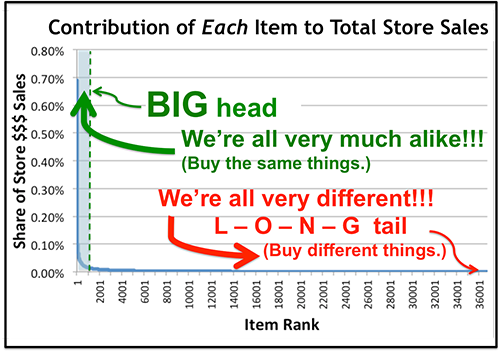

The question speaks volumes to the poor understanding retailers have about shoppers in their stores. The right question should be, how do we get the products the shoppers want to where they are spending time? But that addresses other issues we are not discussing in detail, here. See: How to Sell the Few, Among the Many? The point is that this "shopper density" map is an accurate map of the time shoppers spend in the store. All those blue, and especially the dark blue areas, represent parked real estate capital, regardless of how you propose to manage it. The bottom line is that retailers have massive parked real estate capital, while online retailers have no need for that unused walking space that serves shoppers poorly - actually impeding their purchases in bricks stores - and represents dead weight sunk capital to the retailer. "Parked Inventory" Capital The data and map above are relevant to both inefficient use of floor space capital, but also are directly related to the massive unmoving inventory on most stores' shelves. The building of larger and larger stores has been driven more by the desire to offer more inventory - requiring more space - on behalf of the brand suppliers, who are paying for the space and other marketing services. It is NOT needed to accommodate the demands of the crowds of shoppers. In fact, there is actually a competition for space within stores between shoppers and products. See: "The Aisleness of Stores." It should be obvious: all the space occupied by inventory, cannot be occupied by shoppers! And shoppers do like, and are controlled by, open space - see: Who enjoys shopping in IKEA? (18 Jan 2011) - watch 90 seconds. That video provides solid evidence that shoppers move around stores, not in search of products, but looking for open space, probably subconsciously expecting that the open space will lead to at least something they want to buy. This is a crucial point. But, just as we looked at the usage of the floor space of the store, let's look at their usage of the inventory in the store, another massive sponge, in this case for working capital. Here is what is actually happening with the total store inventory - and this is VERY similar for any store in the world.

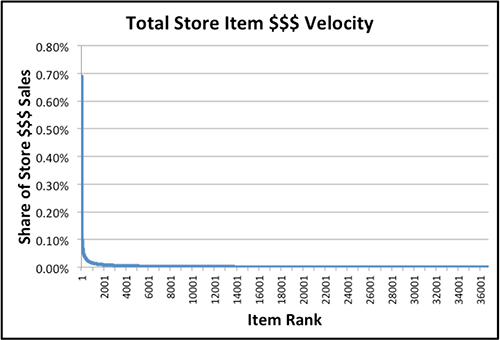

The chart on the left shows the share of total store sales contributed by every single item in the store. For this store, the #1 selling item reaches a whopping 0.7% of sales!!! (If everything in the store sold at this rate, it would be a $5 billion store. ;-) But, as you can see, sales for individual items fall precipitously as items in the store multiply. You can read about the management of sales for those items on the left side of the chart, the so-called, "big head," here: "Deciding What to SELL!" and in the earlier cited, "How to Sell the Few, Among the Many?" Now let's look at what is going on with the shoppers, that drives this curve. Understanding this is important to understanding why the curve has this shape, the proper management of the merchandise in the store, and a good deal more:

This is the same chart as the other one above, only blown up and annotated to make clearer the distinctions we need to make. Proper distinctions are the key to super performance. First of all, you'll notice that of the 36,000+ items in this store, something like 1000 are delivering about 60% of the store's sales. That is, 2.5% of the items in the store are delivering 60% of the store's sales. But the reason for this great disparity in sales between these few (the "big head,") and all the rest (the "long tail,") is driven by some fundamental facts about human beings in general, and the shoppers in this store specifically: We're all very much alike! Hence, we all buy much the same things. This similarity amongst the population relentlessly drives the Big Head, the Pareto Principle, the 80/20 rule (20% of the input drives 80% of the output.) Of course it isn't always an exact 80/20 ratio, but winning products, like winning efforts, are far more productive than "the madding crowd" of products on the shelves. Failing to distinguish amongst these things, failure to distinguish the "winning products" from the "less than winning products - a.k.a. losers" is a virtual guarantee of mediocrity - which is rampant in the self-service retail world. This is true even for the market leaders, because their major competition has been stuck in the same capital inefficient paradigm, for a very long time. So although long tail items are winners for small numbers of shoppers, or occasionally, we must label them "loser" products that are, in fact, a drag on store performance. Two classes of merchandise: the BIG head; and the L - O - N - G tail "Winning products" the Big Head, are those that efficiently serve the massive needs shared, in common, by the largest share of the shoppers. However, as important as "We are very much alike" is, there is also significant value to the great differences among us. Those great differences are the sources of innovation, creativity, etc., that may result in future winners. But, more importantly, in the here and now, they make someone(s) very happy. Every one of us has interests in some very Long Tail products, that appeal to only a tiny slice of the market, and possibly, only on rare occasions. We are all very different, and attracted to different products. I can illustrate this by my own need, recently, to purchase a "cat-house," for an adopted abandoned cat. First, we visited Walmart, Petco and Coastal - a farm supply store. We looked at a couple other places, too, and didn't find what we were looking for. So, off to Amazon:

And... in a flash, Amazon coughed up more than 7000 entries, related somehow to "cat house!" I scanned the top couple dozen - listed in sales rank order - and pretty quickly decided that the first item in the list would do just fine for us. A couple days later it was delivered to our door, my wife impatiently ripped it open and set it up, and the cat endorsed the purchase by immediately moving in! (And it's even heated for the few bitter cold days we have in the winter.) Now, I have never purchased a cat-house before, and probably never will again. And I seriously doubt that Amazon carries a huge inventory of this particular item, scattered from hell-to-breakfast across the country. But they efficiently delivered just what I needed, of what must be a rare item in terms of total sales, especially in the bricks-and-mortar stores I visited, and NOT one of those stores carried this particular item! Pretty shocking, eh? But pretty routine for Amazon, "The Everything Store!" Do you see the problem for the bricks-and-mortar stores. Even with trillions of dollars of inventory capital deployed across the country, they can never compete with a merchant with a thousand times longer tail, very sanely managed, (from the shoppers point of view.) And the irony here is that shoppers do not go to stores because they have the Big Head products buried somewhere in the store. Even though they go to the store to buy the Big Head items, they go there because they subconsciously expect that anyone who has those 40,000+ items, almost certainly will have everything they want!

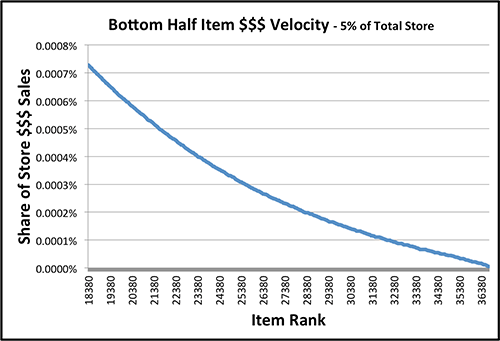

For the supermarket, the bottom half of the inventory behaves very differently than the top half, delivering only, collectively, about 5% of the total store sales. Simply, this means that all that merchandise is spending a lot of time sitting around doing a whole lot of nothing, in terms of going home with shoppers. Don't overlook that those 18,000+ items at the bottom of the sales curve, deliver from 0.0007% of sales, more or less steadily down to 0.0000% of sales - less than 0.0003% of total store sales, on average! As noted above, these do play a role in attracting shoppers to the store, but as far as economics are concerned, it is "parked capital." [Note: An indeterminate number of items do not even show up in the transaction data at all, even over the two year period represented by this data. That is, there are hundreds, if not thousands of items, to the right of that 36,000, with zero sales for the period. That's truly parked inventory! ;-) These facts have led to my suggestion that maybe all those products should be removed from the shelves, and replaced with attractive photos of them, maybe on window shades to cover all the resulting empty shelves! ;-) This is of course hyperbolic, but suggestive of the baleful effect all this "parked inventory capital" has on the financial performance of the store. With the next Views, dealing with the solution to the problem, I will outline how some bricks retailers are making weak, but worthwhile efforts, to address the sales part of the problem, but still ignoring their massive parked inventory problems. And how other bricks retailers have long solved the parked inventory problems, and yet are vulnerable to the everything long tail. Other than reading this current issue of the Views, it would be helpful to review Selling Like Amazon... in Bricks & Mortar Stores!

Here's to GREAT "Shopping" for YOU!!! |